-

Posts

5,195 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

11

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by Doug

-

And free Hunter campaign. Now into buying more vote.....Student loan forgiveness.

-

This weather is getting depressing. Did some needed brushing today so we don't clip off a mirror or light. 48 deg.

-

Our club president bought this for his great grandson.

-

Had a 2021 VR1 and because of the late delivery of the 2022's the sled had 6500 miles on when it got traded. Know where the sled went and its still good without any issue. Keep an eye on the jackshaft bearing and there's good information on what to look at.

-

Any other Ride Command trail managers here?

Doug replied to Bontz's topic in General Snowmobile Forum

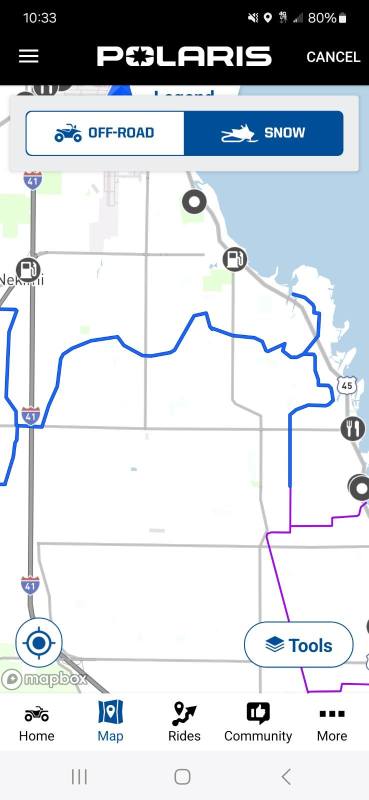

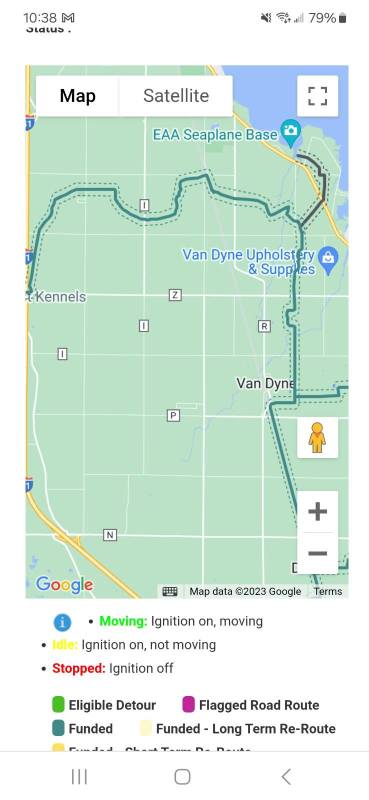

Plugged on the GPS on the qudtrac today for a little to make sure everything worked. Green would have been tracking correctly. Yellow was traveling to slow or stopped which I was moving a sign and taking a picture. If I was actually grooming I would just review the report to make sure its correct and then send it into our County Parks where our club would receive the money. -

Neighboring club asked if we could try leveling out there trail. Did what we could wish they would have asked earlier for better results. Seen an Eagle in a tree. And one of their landowners was having shit put on their field with a stuck truck. Quadtrac to the rescue. Driver had to lay in shit to hook up to the tractor. 💩

-

So in Colorado you have one that is legally not able to serve as president and one that is mentally/physically unable to serve as president.

-

The Man – Doug Hayes: Doug Hayes began his racing career racing Ski-Doos in stock and modified classes out of the family Ski-Doo dealership in Crandon, Wisconsin. Showing strong early talent, Hayes won the 1965 North American Championships at Munising, Michigan, as a 13-year-old and posted five consecutive Mod I titles in USSA oval racing in 1969-1973. Racing as a member of the Larsen-Olson Polaris team, Hayes was part of the winning Soo I-500 team in 1972. Doug moved to Mercury in 1973 where he began to work on the legendary Sno-Twister project. Doug and his brother Stan became a highly successful development and racing team for the Mercury factory in Fond du Lac, WI, with the pair posted dozens of Sno-Pro oval track victories including a sweep of their classes at the USSA World Series and a repeat victory at the Soo I-500 in 1976. Named to the Ski-Doo factory team in 1977, Hayes won the Dr. Pepper Sno-Pro series opener at Kinross and won the prestigious Hetteen Cup enroute to a runner-up WSRF High-Point title before switching to cross-country aboard an Olaf Aaen-sponsored Polaris Indy to finish his racing career in 1979. Doug Hayes was inducted into the Snowmobile Racing Hall of Fame in 1996. The Machine –1975 Mercury PDC factory race sled: This Mercury race sled represents the proof-of-concept design direction for the 1976 production Mercury SnoTwister models. In 1975, the Mercury High Performance Group, which was not considered the Factory race team but was the Mercury Snowmobile R&D team – was tasked to design and build oval-specific liquid-cooled race sleds and confirm the design potential by competing in the Professional Drivers Circuit (PDC) against top factory competition. Following the season, Mercury requested that one snowmobile be saved for its product archives, and the others to be destroyed, so this machine is the only survivor of the six race sleds built. Doug Hayes assembled this SnoTwister from the best remaining parts from each of the team’s sleds, including his original #5 hood. It is currently on display at the Snowmobile Racing Hall of Fame through the generosity of Mercury Marine. The Hayes family has a rich history in snowmobile racing – How did it all start? My dad, George, had a gas station and repair shop here in Crandon Wisconsin. He had a strong technical background, especially in electrical systems. He was rebuilding starters, alternators, and generators along with general automotive repairs. He also had a lathe and other machining equipment in his shop. Dad was mechanically gifted and very much a ‘hands-on’ guy. One of his customers had a Polaris dealership over in Rhinelander and said “George, you need to take a ride on a snowmobile the next time you’re in town, I think you’re going to like it.” That winter the family made a Christmas shopping trip to Rhinelander – Mom and Dad with Stanley (age 13), me (11), Gene (9) and Terry (7). We stopped at the Polaris dealership and the owner took out a K-70 SnoTraveler (a small-at-the-time model with a Kohler engine in the back). The dealer gave Stanley a ride, then I got a ride. After that, he told my dad to go and take Gene and Terry out for a ride. My dad said that he couldn’t care less about riding the damn thing – but anyway, the dealer insisted so my dad and the boys took off. When my dad came back, he said “I think I got more excited than the boys did!” My dad was the one that really got hooked. So, in the summer of 1963 dad got set up as a Polaris dealer. Back then you had to take three sleds to get started and I believe we sold 8-10 snowmobiles that first year – the interest just took off! Tell us about the first Eagle River Snowmobile World Championship race: It was 1964 when the first Eagle River race was held on Dollar Lake, and Polaris was there with a full crew from Roseau. It happened that we had one of the wide track Polaris models with an Onan twin cylinder engine on consignment from Polaris to see if we could sell it, so Allen Hetteen asked us to bring it to the event and said that Stanley could run it if he wanted to. When we got there, we were surprised at the amount of interest. Besides the Polaris crew, who had brought down a bunch of their sleds to participate, there were people from FoxTrac, Evinrude and even Roger Skime from Arctic Cat came out to Dollar Lake for that first event. Anyway – we got there, and it was so cold that the Onan just wouldn’t start, and Stanley aggravated Allen to the point that Allen finally said, “Well hell, we got this 7 hp model that you could run if you want!” Stanley did run that 7 hp Polaris and ended up winning the event overall – he won the first Dollar Lake race so from then on, our family was hooked on racing these new-fangled snowmobiles. The next year, Polaris came out with a new front-engine model called the Comet – and that model was a disaster! We saw first-hand that snowmobiles were nothing but a lot of work. Dad would open the shop on Monday morning and every single sled I sold the week before would be sitting broke down out in the parking lot and the folks wanted them fixed. After that 1964 season my dad had had enough and said, “We can keep a couple of sleds around to ride and have fun with, but we are done – we are not going to sell snowmobiles anymore!” However, in the summer of 1964 a Halverson Equipment salesman, working for the Ski-Doo distributor out of Duluth, MN, stopped by and really wanted my dad to become a Ski-Doo dealer. Dad said he didn’t want anything to do with snowmobiles, but the salesman was persistent. Eventually my dad said “Well, I’ll take two sleds to try them out to see if they are any good.” The salesman had set the hook but came back with “No, you have to take a minimum of three sleds to become a dealer.” Could be that my dad had four sons that could ride them if they didn’t sell, but eventually he did sign up to get the three new Ski-Doos. It worked out OK because we did sell 8 or 10 Ski-Doos that first year. As a new Ski-Doo dealership, did you guys start racing right away? We were always a competitive family, so when Dad’s cousin, Lute Ison, used his performance knowledge from racing outboards to get his Ski-Doo to go faster, the need for speed was there. First Lute would be the fastest so we had to do something to get our sled to beat him, and the game was on – we would go back and forth changing stuff just to beat each other. We were feeling pretty competitive, so we entered our first stock-class race, with Stanley on a 1965 10 hp Olympic and me on an 8 hp Chalet. Wouldn’t you know it – the other stock-class race sleds weren’t stock! After that race my dad said, “That’s never going to happen again!” Dad bought every book he could to learn about two stroke engine modifications. He started by cutting the heads, upping the compression, opening the ports, changing the ignition timing, gutting the mufflers – things like that. It got so our stuff was running pretty damn fast and we were winning a lot of races so my dad’s ability to build fast sleds was getting noticed. What was a snowmobile event like back then? In 1965 nothing was really organized. The local men’s club or Chamber of Commerce would lay out an obstacle course and we would race around pylons. Some events would have a bigger course staked out around a lake and you would race as a group for two or three laps to determine the winner. Another event was kind of like broomball, but you would have two guys on one sled, the rider would have a broom and you had to control the ball through a set course – whatever team got through the fastest won. There may have been only 20-30 competitors across all classes, with 6-8 racers in each class. I ran the Chalet in the 8 hp stock class, with Lute and Stanley racing in the 10 hp classes, with all these sleds running similar internal engine modifications. Lute entered the 10 hp stock class and since Stanley also had a loud, gutted muffler, Stanley entered the 10 hp modified class. This was the time that my dad got into exhaust tuning – the gutted muffler actually ran faster than the typical straight pipe or megaphone exhaust that was common back then. Anyways, that’s how we all got started in racing. My dad just kept modifying engines – cutting heads, porting cylinders, and going to over-bore pistons – he would make changes and then test the results with side-by-side runs. Eventually we had so many seized cylinders that he bought a boring bar machine so he could resize them himself. In 1966 the sport was really getting popular; our Ski-Doo sales were growing, and the races got bigger and much more organized. For example, we went to Munising, Michigan and they had a 50-mile cross country event held on Saturday. The race started out of downtown Munising and went out to Grand Island and ran a lap on the island and back to town. On Sunday they had an oval event and a timed obstacle course event. In the end, I won all three of my classes on my 10 hp Olympic and was crowned the North American Champion. What was the level of competition? By 1966 all major manufacturers and many local distributors had race teams at the major races around us. There was an early season race held in an ice arena in Duluth that was a big deal, so Halverson Equipment asked Steve Ave to scout for promising Ski-Doo racers. Steve set up tryouts in Hurley so Stanley, Paulie Spenser, Dick Bahr and I went up there to run, with the idea that if you did good you could get help from Halverson. Of course, we all did good, so we became Halverson-supported racers and were invited to race in the 1966 Duluth indoor race. About a week before the Duluth race the guys were brainstorming about how to get a holeshot on that indoor ice track. We had rubber tracks, so we couldn’t just add sharpened bolts to the cleats like the Polaris or Arctic Cat guys could do. That was when the first studs on rubber tracks were discovered. Steve Ave’s dad, Tony, had a Sports Shop in Hurley and somebody there had the idea to try the metal golf shoe spikes on our rubber tracks to gain some traction. They tested those spikes and – oh yeah – that really made a difference! Now they had to find enough golf shoe spikes to outfit the team. Steve called Tom Halverson over in Duluth to buy all the golf shoe spikes in town. We were studding tracks on the floor of the arena just before we were to go out to the line to race. We also had a liquid traction product from my dad’s service station that was called Liquid Tire Chains. You would spray this stuff on your tires if you were stuck to increase the tire grip. In addition to the golf shoe spikes, we would spray our tracks with this stuff in every heat to get good hole shots. These tricks worked! I ended up winning my class on my 1965 8 hp Chalet. As an independent team, how did you go racing? Dad said right away “If we’re ever going to get better, we must race against the best”. Being in Crandon, we were pretty much in the center of the action to race against the top teams. On a typical race weekend, mom, dad, and us boys would take off Friday night and come back late Sunday night so my dad could work on Monday morning. It was really a family effort – my dad would work on the engines, my mom would keep track of the expenses, the winnings, the motel reservations, plan the trip, and keep us fed, and us boys would be working on the sleds back in the shop and at the races. We had a pickup truck with a plywood shelf so we could haul two sleds above the box and pull an open trailer with two more sleds. As we got more guys racing out of our shop, we got a larger dual axle open trailer that could haul six sleds on it. Since we could now haul more sleds, we could take more guys, and some ran multiple sleds across several classes. We won lots of races so more local racers came around to get their engine work done. Our racing success promoted the dealership and we just kept growing and growing. Developing tuned pipes: We started competing in grass drag events over the summer. That’s when Dick Bahr started figuring out tuned exhaust pipes – Dick designed and built a tuned pipe for a 1967 10 hp sled that I was grass dragging. The pipe was so long that we had to run a brace off the rear backrest hoop to support the stinger. Even though it ran down the whole side of the sled, it was faster than a straight pipe! Monte’s Bombardier, a western Ski-Doo distributor that also raced motorcycles, was instrumental in building better tuned pipes for their race sleds, so we bought some and ran those pipes as well. Monte’s measured tuned pipes off motocross bikes at the time (Montessa’s, Jawa’s, etc) and transferred those dimensions into a pipe that would fit on a Ski-Doo. Anyway, Dick just kept testing, building, and refining his tuned pipe program and, by working with my dad, they just kept making more and more power. We were winning a lot of races, so more people wanted my dad to do engine work for them. That grew into a pretty good engine mod business over the next two years. How did the Dick Bahr connection happen? Dick was a local customer that bought a 1966 Ski-Doo and raced with us. Well, Dick was a little on the round side and fell off a few times, so he decided to work on sleds rather than race them. Dick got into modding the engines and especially tuning the pipes. He became a master at figuring out the math behind tuned pipe design. He did much more than just pipe design though – Dick Bahr was also an artist along with his many other talents. We had seen the Ski-Doo Factory racers running twin carbs on their 250 single, but we couldn’t buy the special manifold. Dick carved a dual manifold out of wax and made a mold. He then melted down a few of the many seized pistons sitting around the shop, poured the liquid aluminum into his mold and – tada – We were racing with twin carbs! With dad modifying the motors and Dick building the pipes, we kept winning pretty much everywhere we went. Introduction of ‘Factory’ race parts: Ski-Doo came out with the T’NT series in 1968 and Stanley got a 600 T’NT from Halverson to race. The production models had cast iron cylinders but there was also a Rotax ‘Sports’ kit that included aluminum cylinders, new pistons, different heads and came with specifications to build a megaphone exhaust. The new cylinders had a removable plate over each transfer port to machine the improved shape (vs. a ‘cast-in-place’ transfer design). Since these parts are easily identified, the ‘Sports’ kit was only used for modified class racing. However, they also had some other aluminum cylinders that – if painted black – looked stock enough so you could sneak those into the stock class every now and then. Opportunity knocks In the summer of 1968 dad got a call from Mickey Rupp with an offer to head up the Rupp Industries engine department in Mansfield, Ohio. Dad went to Mansfield to see what’s up. On his return, he said “I have never been offered so much money to do something that I really wanted to do.” In addition to dad’s pretty good offer, Mickey Rupp offered us boys a spot on the Rupp factory race team. Dad’s cousin, Lute Ison, heard about what was going on so Lute called up Tom Halverson and said “George Hayes is going to Rupp!” Tom said “Lute, you tell George not to sign anything – I will fly down tomorrow and pick George up at the airport.” Tom Halverson made my dad an offer to oversee the Service and Racing departments at Halverson Equipment. Dad’s job was to get engine mod specifications out to all the Halverson dealers, and to do future engine development for the 1969 race season, and a part of dad’s deal was that Stan and I would race on Gil Hartley’s Red Diamond race team running out of Halverson race shop. Well, my dad would rather stay with Ski-Doo and, as a family, we would rather move to Duluth than Mansfield, Ohio. We made the move to Duluth in the Fall of 1968. Dad’s move to Halverson Equipment: Managing the Racing and Service departments really increased dad’s exposure to the key people and latest technology at Bombardier and Rotax. For example, Bombardier would host the key distributor’s performance people in Valcourt each fall to do engine development. Every distributor sent people to this Factory-supported workshop and shared what they were doing to increase performance. Since Halverson was the largest Ski-Doo distributor and Steve Ave and Laurent Beaudoin (the Bombardier president) were like best friends, Valcourt was constantly sending us stuff to test. We had many one-of-a-kind Rotax engines in the shop to be evaluated. They weren’t legal to race but Bombardier and Rotax wanted our feedback, so we ran them against our race sleds. Anyway, we moved to Duluth in the fall of 1968 and dad had a free hand to modify the 1969 models into our race sleds. I had a 295, Stanley had a 340 and Steve Ave had a 669. Back then, all Rotax production engines were fan-cooled, but my dad wanted to race free-air race engines. He went to local motorcycle shops in search of free-air heads that were close to our cylinder specs and modified them to fit our engines. He then went to work on the flywheel, removed the magnets and designed a constant loss ignition system using a battery and an automotive ignition coil, but kept the standard points for ignition timing. Those changes dropped a bunch of weight off our engines. He then pushed out the cast iron cylinder liner and ground the aluminum exhaust port super wide. Cutting two windows in the iron liner allowed us to run triple exhaust ports for better exhaust flow. For the transfers, he ground passageways from the base of the crankcase that came out right above the intake port. For the exhaust system, he tries various tuned exhaust pipes, either from Monte’s Bombardier or directly from Rotax. These modifications really worked, and Stanley and I raced those engines at a time when Polaris just dominated everyone due to their new flyweight clutches. We were the only Ski-Doos that could even run close to them, so of course we got protested and tore down every single weekend. Did you run any alcohol motors back then? In 1970, all the factory teams were running alcohol fuel. Again, dad researched and modified the carburetors to deliver more fuel, as it takes almost 3 times as much alcohol as gasoline, but you can make more horsepower by changing the compression and ignition timing, and the added fuel really kept the free-air engines running cooler. At the last race of the year, with all the factory teams there, I was running my 340 Blizzard with my dad’s latest engine mods and an alcohol carb set-up. At the start of my race, I was hit by a competitor and got tipped over, so now I was dead last with a factory Ski-Doo driver out in the lead. Steve Ave was standing next to Laurant Beaudion (Bombardier CEO) and Laurant said “Ski-Doo will win this race!”. Steve replied, “Yes they will – but it won’t be your driver.” I drove my Blizzard from last to first – and passed the Ski-Doo Factory driver with more than a lap to go. Laurant turned to Steve and said, “Have George Hayes remove that engine and bring it to our Team truck – it will go to Valcourt tomorrow!” After the Ski-Doo success, why switch to Polaris? At the end of the 1971 race season, Halverson stopped racing. With that change, we all moved back to Crandon. One Saturday, dad got a phone call from Bob Eastman at Polaris. Bob would like to offer dad a job in their engine department. So, dad and I drove to Polaris and met with Bob Eastman and Jim Bernat. Dad declined the offer but suggested to call Dick Bahr. They did and Dick moved to Roseau to work in the race department on engine development. Bob also contacted Herb Howe at Larsen-Olson (a Midwest Polaris distributor) and Stan and I were placed on the Larsen-Olson team for the 1972 racing season. Any Larsen-Olson highlights? In 1972, I raced in Mod I (295cc) and Mod III (440cc) and Stan raced the Mod II (340cc) and Mod IV (650cc) classes. Stan had a solid year with both of his sleds, which earned him a move up to the Polaris Factory team the next season. My Mod I race sled was very competitive, but I struggled with the 440. Eventually we found out that the 440 crank was out-of-phase, probably from blowing a belt early in the season. Overall, at the end of my 1972 season, because I had won the Mod I high point championship for three years in a row, USSA awarded me #5 as a lifetime number. I would race under the #5 number from then on. Bob Eastman offers a Polaris Factory ride for the Soo: Back then, the Factory guys looked to distributor teams for new talent. In our case, Mom came out to the shop and said, “Bob Eastman called and wants to talk to you.” Bob asked if Stan and I could run the Soo I-500 race on a factory-prepped race sled. At 18-years old, it was a pretty cool feeling to be invited to ride with the Polaris factory boys. I said “Yes!” right away but then thought about a possible problem. Back then you couldn’t just jump up to run the 650/800 classes – you had to be pre-qualified by the USSA driver-review board. While Stan was already competing with his 650, I was only racing in the 295 and 440cc classes. I called Bob back and said that I needed that higher driver rating. Bob said “You don’t worry about that, when you get up here, you’ll have a license. I’m the head of the driver-review board.” It was a real morale boost that Bob felt I was qualified to run the big sleds. Racing the Soo: For 1972, Stan and I were teamed with Laverne Hagan, who built the sled and was a Polaris test rider in the winter, so he knew what it took and was in racing shape for sure. Laverne qualified third with triple tuned pipes and a cleated track on our sled, but for the race we put a three-into-one muffler and a rubber track on it. The race was an absolute blast. Back then it was completely a snow track, the straights would get all pounded out and, as your carbides went away, you just went higher and higher up the banked corners. With that quieter muffler, we could just sneak up on everybody – they didn’t even know you were there! We had a 650, and some of the guys were running 800s and could pass us on the straights, but eventually they would start breaking stuff – we just ran solid lap times all day long and we never broke anything. So, by the end of the race, Laverne, Stan and I were the winners! In 1973, Laverne was set to defend his 1972 victory and I was asked back as one of the riders. However, my brother Stan – now a fulltime Polaris Factory racer – couldn’t join due to the PDC oval race schedule, so we had an Enduro racer from Michigan fill out our team. Laverne brought us an awesome race sled – it was a 1973 Starfire with a Dick Bahr-prepped 800cc triple cylinder motor! Dick’s goal was to deliver massive torque across the power curve. He said, “I built you an 800 and that thing could pull stumps. You could gear this for 200 mph and it will pull it!” That sled was really fast – Laverne went out on his qualifying run and just annihilated everyone! He set the fastest time without even trying hard. Laverne started the race in the front row and never even got out of the first turn. He got tangled up and went for a tumble, with him and the sled going end over end. Luckily, he didn’t get hurt bad, but the sled was a mess. We got the sled back in the pits and pieced it together as best as we could, but Laverne was hurting too much to keep driving. Del Hedlund, who was the Polaris race team manager for this event, sent the Michigan driver out on the sled. The pace was really slow, there was obviously a problem, so he was called back in. When asked what’s wrong, he said “I can’t see!” For sure, the snow dust was so bad that no one could really see much – that was just the way it was back then. Finally, Del sent me out for my stint, and I was just a young kid that felt bulletproof, so I just went wide open – just hammering it out there. Eventually Del saw the best way was to put me in for 50 laps, switch drivers on a much shorter stint and then I would go back on it for my full stint. Basically, I raced that 800 all day long and got us back into the top-10, but after blowing the chaincase late in the race we ended up with a DNF (did not finish). I had so much fun racing that sled – it was a rocket ship, it was so fricking fast that we had top speed on everybody, and that Starfire chassis just blasted through the big bumps like I was in a 500-mile cross country race. Once you race the Soo you are hooked and want to race it again and again. The Mercury Years The 1974 Mercury SnoTwister was to be introduced and Mercury contacted Lute Ison, Paul Spencer and myself about racing this new model in the ‘74 season. We met and ran a pre-production sled on the grass, and it sure didn’t take us long to accept Merc’s offer. My season highlights included winning overall points in the Mod 1 (250cc) and Mod 3 (440c) classes plus high point driver of the year. I also won the Mod 1 at the World Series race held in Eagle River. When the race season was done, Lyle Forsgren asked me to go on the road and help to finalize the calibration of the 1975 SnoTwisters in Minocqua, Wisconsin, Flin Flon, Manitoba and Cooke City Montana. After testing was done, Lyle asked if I would work full-time in the new Mercury HPG (High Performance Group) that he was putting together. Of course, I said yes. Our job was to design and develop the production racing SnoTwister model to be introduced in 1976. Testing in Cooke City, MT When I first went to Mercury, I worked in the Advanced Research department with Bob Mendlesky and Dr. Bob Kern. One of Dr. Kern’s jobs was to develop software to calculate the correct calibration of our CVT clutches – which were Arctic Cat hex drive clutches at the time. Bob would change the drive clutch ramp angle and length and not tell me what he did, then we went to the field and collected stopwatch data, noted the tach reading, and comment on my seat-of-the-pants feel at each set distance. I would then give them my feedback, and Dr Kern would work out how to predict the results using his newly developed software program. My brother Stan left Polaris to become the manager of the HPG shop. Jerry Witt and I fabricated the dies to stamp out the bulkhead side panels, and I did 90% of all the welding and machining of the parts needed to build those 1975 race sleds. Stan designed the cast magnesium chain case for our race sleds and Mercury did the casting in their foundry. The chaincase design was the first thing that had to be done when Stan got to Mercury because Mercury only cast magnesium once a year. After the HPG shop was completed, we started building our test sleds for a trip to Alaska at the end of October. We built those prototype sleds with different caster and camber angles on the front cross tubes, different engine location, different rear skids and tracks for this test. Parallel to our chassis development, Dr. Les Cahoon and Dick Bahr were doing engine performance testing on the Kohler engines used in our race sleds and eventually in the 1976 SnoTwister models. The Kohler engine was based on a platform that started out as a 340cc engine making around 30 to 40 hp. Dick and Les brought the displacement up to 440cc and were producing close to 90 hp at 10,000 RPM. We would experience many engine failures that season, but by the end of the year even more performance was found along with increased durability of the engines. After we returned from the Alaskan trip, it was 16 to 18+ hours a day to build our six race sleds for the season. The first race of the season was in Rhinelander. This meant we had less than a month to get six sleds ready to race! We did have the major parts built up before the Alaska trip such as chassis and bulkhead with the chaincase, rear suspension rails and tracks in place, but we still had to make the front suspension crossbeams, rear suspension front torque arms and motor mount plates for the final engine location. Dick was still working on our race engines and pipes until the week before we had to head up north for setting the race-spec clutching and carb calibration. As I recall, it was just one or two days before the first test trip that Dick finished the 340 and 440 mod engine packages. Dick brought these first-generation race engines to the HPG shop in the afternoon, and we started fitting the dyno pipes to the chassis. We worked until around 2 AM until all six sets of pipes were finished. The sleds were finally together, but we still needed a place to test. The ice on Mole Lake was good, so we ran there for a few days. From there we went to the Mercury test site in Minocqua to prepare for the first race in Rhinelander. First race on the 1975 SnoTwister We had good results for our first race – I took first in the 440X class, and we were very competitive in the PDC 340 and 440 classes. Early problems were Kohler cylinder breaking at the base, lower end rod bearing failures, Prestolite ignition failures and we tried adjustable main jets on the carbs that didn’t work! The mod cylinders breaking off at the base mount was because Dick had carved out the intake ports so much that there wasn’t much left to the flanges! This was cured by running bolts from the crankcase through to the cylinder heads. This would sandwich the engine together and stop the breakage completely. Silver plating the rod bearing cages and thrust washers dissipated enough heat to keep them running. We changed back to the standard Mikuni float bowl carburetors to get our calibration in line, but unfortunately, we had to run the Prestolite ignition systems for the rest of the year. The ignition problem was that timing would change when the temperatures dropped. The chassis and rear suspension designs were under constant development during the race season and many ideas were conceived during our after-race debriefs while sitting around a restaurant table. Diagrams would be sketched out on a napkin and then we would build the next generation rear suspension in the HPG shop. Clutch calibration was being worked on constantly as new engine mods were evaluated. At the end of the season, the race team built up the 1975 #5 PDC-spec race sled to these final specifications to go into the Mercury product archives, which is the sled currently on display at the Hall of Fame. 1975 PDC Race season highlights: I won the 440X class at the first race of the year held in Rhinelander, Wi. Stan qualified for the Eagle River World Championship race with his 440 Mod sled against the 650cc competition and finished 3rd overall. As a team, we had many podiums throughout the year, and finished strong at the USSA World Series in Weedsport, N.Y. I won the Mod 340 class, Stan won the Mod 440 class, and I finished 3rd in the same 440cc class, but on my 340 Mod sled. Doug Hayes, Jim Bernat at Eagle River Mechanic Bob Mendlesky, Doug at Weedsport Setting the 1976 SnoTwister specs: Dick Bahr had finalized the future 1976 liquid-cooled production engine port timing and we raced those specs in our free air engines to confirm them. We also were running the basic chassis and suspension specs that would be incorporated into the 1976 production SnoTwister models. After the race season was done, we had to transfer the race sled design direction to the 1976 SnoTwister specifications. We had finalized the front bulkhead and crossmember design earlier in the year but were still validating the rear suspension and waiting for prototype test tracks from Goodyear. Our final validation test was done on Lake Winnebago in late March after we received the Goodyear tracks. Very late that Spring, we went to Crandon and did durability testing on Lake Metonga, then out to Cooke City, Montana for more durability and high-altitude carb and clutch calibration. Mercury would make 250, 340 and 440cc sleds to compete in the USSA stock racing classes. To race as production-stock sleds, they had to meet all government requirements for trail usage, including the sound and lighting requirements. Dick had been working on the new Kohler liquid cooled engine specs all summer and was getting great power on the dyno. Dick had made his target horsepower numbers for each of the engine sizes, but after running the pipes into the muffler, some of the performance was lost. After looking at an existing silencer design from Donaldson muffler, he had an idea to reverse the flow of the exhaust through the silencer and there was very little power loss with that layout. We were all set to release the pipe specs to make the production tooling when Les Cahoon received a tip from someone at Kohler that Arctic Cat could not get the horsepower number that they wanted for their 1976 Kohler-powered 250cc stock racer. If Arctic Cat could not meet their horsepower target, they would not purchase the Kohler engines! So Kohler called Les and said Kohler needed the final Mercury pipe specs to do durability on the new-for-1976 250 liquid cooled engines. About a week after Les released the pipe specs to Kohler, Les received a call that our pipe specs went right to Arctic Cat so Kohler could get the contract to sell them engines! Dick went back on the dyno and changed pipes again and came up with another two horsepower for the Mercury 250cc engine. Gaining a two-horsepower increase on a 250cc engine, one that still met the production sound level requirements, in about a week was a very big deal! 1976 SnoPro race sleds: Lyle Forsgren calls a team meeting Building a future that didn’t happen: Hearing that the Mercury pipe specs were sent to Arctic Cat, Les said “We will have our own engine design! No one at Mercury was to give Kohler any information on our engine work from this day on!” – and he started designing a Mercury-only snowmobile engine. By the fall of 1975, Les designed an engine with the parts to be sourced from Europe and then assembled at Mercury. The overall engine design was very compact due to its short stroke (vs. Kohler). Specific design features included a bridged exhaust port, an intake port design that allowed a reed valve or piston port option (Two different intake systems allowed the engine to be used for both consumer and racing) and a high mass Thunderbolt ignition system with the greater degree of ignition advance/retard timing built into it. At the end of February 1976, Les had the first-generation prototype engines running on the Mercury dynamometers. Unfortunately, Dick was only able to do preliminary dyno runs on this engine and there just wasn’t enough development time before Brunswick shut the snowmobile division down. Dick had also been working on the latest Kohler engine specs for the 1977 production race sleds and needed to validate the engine specs on a sled. It was decided my brother Gene would do this test. Dick sent dad the cylinder heads and pipes to build Gene an engine. They received the components one week before the Wisconsin Governor’s Cup race in Wausau Wisconsin. Stan and I also went to that race on Saturday morning. When we got to the track, Gene and dad still didn’t have the sled completed, so Dick, Jerry Witt and Bob Mendlesky went to work on it. Dad and I pitted for Gene with his stocker as the rest of the HPG guys finished up on Gene’s Mod sled. Dick was heat-cycling the new engine to break it in on the jack stand and we used Gene’s Mod III qualifying heat races to dial in the clutch and carb setting – Dick was on the jetting, and I was on the clutching. Gene won his Stock and Mod Stock races with a stock 440 and then went on to win Mod III with Dick’s new engine specs. In the special Governor’s Cup race, Stan and I would run our factory Mod III SnoPro sleds against Gene on his sled with Dick’s new engine specs. Gene hole-shotted the group and led every lap. Stan was second and I was third and Gene’s teammate, Paul Spencer, was forth. Dick’s 1977 engine specs have been verified! Lyle set us to work on the 1977 Sno Twister Production race sled chassis and suspension designs, along with more cross-country racing to develop a better consumer trail sled. For the 1976 race sled, we had moved the radiator down in front of the engine to lower the center of gravity, tried a shorter wheelbase by using a different bulkhead, we installed tracks as short as 101”, and ran many different rear skids. We took the bulkhead dies we had made for the 1975 PDC sleds and pulled the front cross tube back around 2 inches. On the rear skid, we tried split front and rear torque arms so there would be more independent movement of the rails when turning, along with different front torque arm lengths and locations. By the end of the 1976 race season, we decided we went too short on the overall wheelbase and track length, so we planned to go longer wheelbase and longer track for our 1977 SnoTwister production models. Lyle Forsgren also decided to develop a cross-country sled direction, so we didn’t travel east to race those oval events. We built sleds for the Winnipeg to St. Paul 500-mile race, the Heartland Grand Prix, Soo I-500 enduro oval race and the Mackinac City 150-mile enduro oval race. The sleds for the Winnipeg race were 1975 free air SnoTwisters. Tom Wehner, Mercury’s snowmobile race support manager, finished in the top 10 with one of the HPG sleds. At the Mackinac City 150 race, we put a 110-inch TrailTwister rubber track and a modified rear suspension into one of our SnoPro 440 sleds. I qualified fifth and we led every lap of the race to win. Victory photo at Mackinac 150 race Tell us about the Soo race: Stan and I told Lyle that we just had to run the Soo. It’s basically a 500-mile cross-country race so we could test our cross-country design direction, plus it’s an awesome event – you get to race all day! In 1976, the maximum engine size was 650cc, but the largest engine Mercury had was a 440. No problem, we put a liquid cooled 440 Kohler in the 1975 SnoTwister cross-country chassis, a radiator, big windshield, 110” rubber track and a SnoPro quick track-change chaincase. Our 440cc engine was basically stock, but with tuned pipes. To win, we knew we had to run consistent, fast laps all day, but we also wanted to be prepared for any problems. We loaded up extra engines, hoods, tracks, skis, clutches – you name it, we had it! Lyle sees everything laid out, shakes his head, and says “I thought the plan was to run consistent lap times and NOT have any problems! You guys have enough parts to build another sled!!” He was right, we did have enough parts along to just about do that. One example of our race prep – we ran Arctic hex drive clutches, and they would wear over that many race miles. I pre-ran the sled and calibrated three spare drive train sets, consisting of drive, driven and v-belt, tuned to run either above, below, or right on the peak power RPM. If we were losing RPM due to clutch wear, we could come in and change out the complete drive, driven and belt as a system. We could change this out just as quick as it took to refuel the sled and we were good to go. We had a great crew at the Soo. Stan, Jerry Witt and I were the drivers, and Dr Les Calhoon, Dick Bahr, Bob Mendlesky supporting us in the pits. We qualified thirteenth for the race and stayed in the top-10 pretty much the whole race. The 650 guys would pass us, but they would eventually breakdown or crash and we just kept on going. We took the lead around the 150-mile point and the race looked well in hand. However, around lap 350 we pitted and the chaincase was out of oil! We topped it off, but it was dry again by the next fuel stop. We knew this was a big problem – the chain is just not going to last! Dick grabbed a tube of grease, packed the chaincase full, put the cover back on and away we went! Around lap 470 it was dark, snowing hard, and the race was red-flagged. The officials asked the racers if we should continue or stop as-is due to poor visibility. Stan was in the lead, so he said that call was up to the other racers. Everyone agreed it was too dangerous, the event was called, and we won the race. Mercury IFS development direction: During the 1976 race season we, at the Mercury HPG group, saw the advantage of IFS front suspension as raced by Villeneuve and Gordon Rudolph, so we planned to evaluate the IFS advantages. Our design direction was to develop a cross-country long travel race sled. The basic layout of the IFS front suspension was drawn up and it was to be of the strut design. Our rear suspension travel target was 6 inches of travel – which was a ton more travel than we had on our oval sleds. I had the first drawings of the rear suspension at the HPG shop and had already completed the track tension validation study and was waiting for the OK to build this IFS cross-country sled when Lyle told us that all efforts to keep the Mercury snowmobile division had been exhausted. That’s when we all knew that the Mercury snowmobile business was done. With the demise of the Mercury snowmobile business, Stan, Dick Bahr and I met with LeRoy Lindblad and Larry Rugland, and we all agreed to come to Bombardier and work with them on the new Ski-Doo IFS race sleds. It’s amazing how much Mercury product development you did through racing! What keeps you busy now? After I stopped racing in 1979, My wife and I had an outdoor power equipment business until we sold it in 2015. We have two sons that went to work in the snowmobile industry. Ryan, our oldest son, worked for Arctic Cat for 18 years before moving to Polaris, now in his 5th year there. Ben, our younger son, has worked for Fox Shoxs, Walker Evans Shocks and is now at Polaris. Currently, Ryan is the manager of development and calibration of 2 cycle snowmobile engines and Ben is the snowmobile technical racing coordinator for snowmobiles. I am still involved in snowmobile racing by helping my son Ben with the two teams he supports at the Soo I-500 races. I have been doing fuel calculation and pit stop strategies for the Bunke and Faust teams at the Soo since 2012, and for the 2014 race I asked my brother Gene to help. Debriefing after that race Ben, Gene and I decided to research the benefits of Aerodynamics, because the sleds were running over 100 MPH. Gene and I started with just one Aero part for the Bunke and Faust teams in 2014 and now we have complete Aero Body works kits for the Soo sleds, available to any of the Polaris teams that would like to run them. Thank you for covering some of the Hayes’ family snowmobile history, your Polaris, Mercury, and Ski-Doo racing efforts, and how your next generation continues to add to the Hayes’ family accomplishments. Congratulations on your well-earned induction into the Snowmobile Hall of Fame. Story by Greg Marier for SnowTech Magazine

-

-

Any other Ride Command trail managers here?

Doug replied to Bontz's topic in General Snowmobile Forum

In Wisconsin the trail money per county is actually held and dispersed through the County Parks department. Clubs turn in all marking, brushing, leveling etc. to their County Parks department. GPS grooming reports are also submitted to the County Parks. We normally get paid around April so Clubs have to carry any expenses through the year which has been a sore spot for some. If the full amount funded per County is not spent the money goes back to the DNR. If Clubs have a lot of grooming and have exceeded their funded amount they can choose to keep grooming. They can then apply for supplemental grooming funds at the end of the season. To apply for supplemental grooming the club has to have a certain percentage of the expenses as grooming based off the GPS reports. Supplemental funds are made up from money returned to the DNR from Counties that have not used up their allotment. Such as Counties in Southern Wisconsin hardly ever use up their allotment where Counties in Northern Wisconsin almost always go into supplemental. Supplemental is paid out after all money is paid out based on the set allotment per County. Then Clubs that have applied for supplemental are evenly distributed out the left over money. This could be 100% or 60% based on the amount in supplemental funds. -

Any other Ride Command trail managers here?

Doug replied to Bontz's topic in General Snowmobile Forum

All the counties in Wisconsin are given X amount of money based on their funded trails. Our county for grooming is broken down by 4 clubs that have groomers. For us we groom other clubs trailer within our county and that's all tracked by GPS. We also groom into a neighboring county which is not included within our GPS. For that we still have to keep a manual log of hours, times and dates. We then turn an invoice into the neighboring counties club for that section where we are paid by that club. They turn our invoice into their county as a grooming expense to get reimbursed. GPS guidelines.pdf -

Any other Ride Command trail managers here?

Doug replied to Bontz's topic in General Snowmobile Forum

We've been requested to GPS our trails and keep them accurate in SNARS so when they are groomed the GPS records the grooming speed and location properly. If we are outside the GPS on file in SNARS we have a form along with the correct GPS that we need to send in to correct the SNARS GPS file. I think SNARS shares their GPS data with ride command as I haven't heard of anybody having to update ride command. Here is our club trail in blue in ride command and also the the GPS file in SNARS with the green background. We had a small reroute last year and both maps are the same and correct. -

Canada government to ban combustion powered vehicle

Doug replied to BOHICA's topic in Current Events

Opps...I thought you charged it. -

Got some seat time in our clubs new to us quadtrac. It will be nice grooming with this thing. Tiling a field that they had to go rather deep and needed a little help with the tire tractor losing traction. First vid actually broke the tow strap.

-

Canada government to ban combustion powered vehicle

Doug replied to BOHICA's topic in Current Events

Then the first place it should start is in Canada's government. A government motorcade of Tesla's. Canada security intelligence on electric bikes. Charge stations mostly likely run by diesel generators. ⛽️ -

****Official Jimmy Snacks Racing 2023 Nascar Extravaganza Thread****

Doug replied to Jimmy Snacks's topic in Current Events

I think the model year rule thing has been diluted down since the manufacturers have to submit their body panels to Nascar for approval. Each year prior to the start of the season manufactures submit the model and body to Nascar for evaluation. Nascar puts these in a wind tunnel to evaluate the drag and downforce of each manufacturer to make sure they are relatively even with each other. A couple years ago and I can't remember the manufacturer it may have been the camaro teams were racing the car before dealers were receiving production vehicles. After Dodge dropped out of Nascar in 2012 some low budget teams were still running the cars and trucks a couple year later.